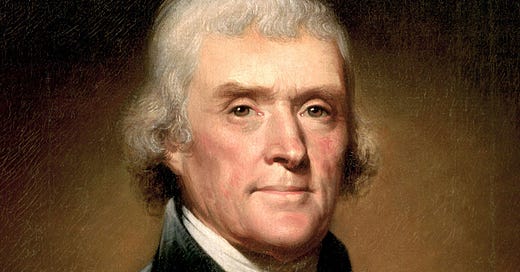

Thomas Jefferson’s Favorite Works of Fiction

A perusing of Jefferson’s letters reveal he was deeply fond of fiction.

Thomas Jefferson was one of the architects of the American system. He wrote the Declaration of Independence (with a tip of the hat to John Locke), helped shape the Constitution, and was a virtual wellspring of the ideas on which the foundation of the United States was laid.

While his knowledge of history and government was profound, the Sage of Monticello chided those who believed “that nothing can be useful but the learned lumber of Greek and Roman reading with which his head is stored.”

In a 1771 letter on novel reading, Jefferson, born on April 13, 1743, suggested that novels could be “useful as well as pleasant”:

Everything is useful which contributes to fix in the principles and practices of virtue. When any original act of charity or of gratitude, for instance, is presented either to our sight or imagination, we are deeply impressed with its beauty and feel a strong desire in ourselves of doing charitable and grateful acts also. On the contrary when we see or read of any atrocious deed, we are disgusted with its deformity, and conceive an abhorrence of vice. Now every emotion of this kind is an exercise of our virtuous dispositions, and dispositions of the mind, like limbs of the body acquire strength by exercise. But exercise produces habit, and in the instance of which we speak the exercise being of the moral feelings produces a habit of thinking and acting virtuously. We never reflect whether the story we read be truth or fiction. If the painting be lively, and a tolerable picture of nature, we are thrown into a reverie, from which if we awaken it is the fault of the writer. I appeal to every reader of feeling and sentiment whether the fictitious murder of Duncan by Macbeth in Shakespeare does not excite in him as great a horror of villainy, as the real one of Henry IV. [Editor’s note: It’s unclear if Jefferson was confusing Henry IV of England with Henry IV of France. The latter was in fact murdered, but it was the former who inspired Shakespeare’s play Henry IV. Jefferson also could have been alluding to Love’s Labor’s Lost, a play of Shakespeare’s that featured a character, the King of Navarre, inspired by Henry IV of France.]

A perusing of Jefferson’s letters reveal he was deeply fond of fiction (in the form of both prose and poem). Here is a list of some of the “modern” literary works he most cherished:

1. The Misanthrope, by Molière

A biting bit of satire that first hit the stage in 1666, The Misanthrope is arguably the greatest literary work written by Molière. (Sassy, irreverent, and hilarious, Molière was kind of like the Larry David of seventeenth century France.)

2. Don Quixote, by Miquel de Cervantes

A Spanish novel penned in two volumes in 1605 and 1615. Still read in college classrooms today, many argue that Don Quixote marked the birth of the modern novel in the West.

3. Gulliver’s Travels, by Jonathan Swift

Swift’s most popular story. The tale, a parody probing human nature, involves a surgeon who travels to the corners of the world and encounters strange types of fictitious peoples, big and small.

4. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, by Laurence Stern

A comedy published as a serial in nine volumes. The first book hit the press in 1759, and the series did not conclude until nearly a decade later. Tristram Shandy is still considered one of the greatest literary works in modern history.

5. The Adventures of David Simple, by Sarah Fielding

Published in 1744, the book is the first and most celebrated story penned (anonymously) by English writer Sarah Fielding (the sister of Henry Fielding). The book became a favorite of Samuel Richardson, who deemed the writer as talented as her brother.

6.The Vicar of Wakefield, by Oliver Goldsmith

A sentimental comedy penned by the Irish writer Oliver Goldsmith published in 1776. The book, which cleverly reveals the innate goodness of man, was one of the most popular books of the Victorian era in England.

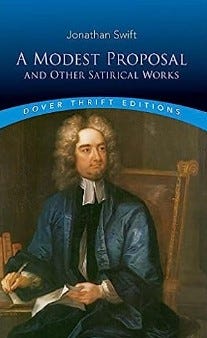

7. A Modest Proposal, by Jonathan Swift

A story penned anonymously by Swift in 1729 that suggested impoverished Irishmen and women might address their malnourishment by selling their children to feed the patrician class.

I'm gratified to know that Jefferson was a fan of Tristram Shandy. It's still a conceptual challenge for today's mind. As Steve Coogan said in his loose film adaptation (A Cock and Bull Story), "It was post-modern before there was a modern to be post about."