Milan Kundera's Greatest Lesson

Kundera understood compassion—its virtue and its curse—better than anyone.

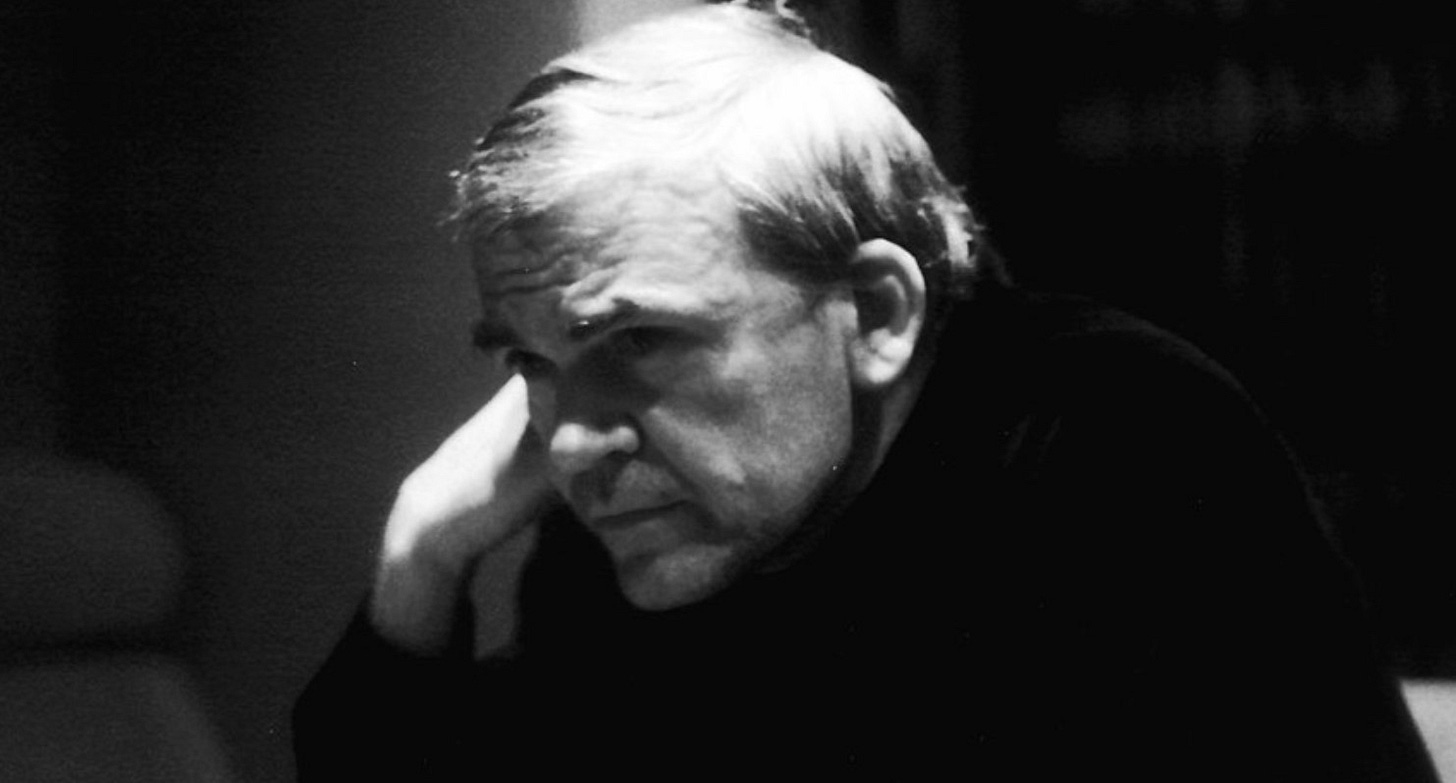

Milan Kundera, the great Czech-French novelist, died this week. He was 94.

I didn’t read all of Kundera’s works, but you’ll find several of his books on the shelves behind me.

His novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being is one of the most honest and powerful books I ever read. The story revolves around the lives of four main characters—Tomas, Tereza, Sabina, and Franz—as they navigate relationships and political upheaval in 1960s Czechoslovakia.

For those who watched the movie (which starred Daniel Day Lewis) the plot is fairly straightforward: Tomas, a successful surgeon and womanizer, struggles with dual desires: to be a faithful husband (which he fails at) and to whet his sexual appetite with his mistress (Sabina).

The movie was okay, but it lacks the deep pshychology that is explored in the novel, including philosophical themes such as existentialism and Nietzschean concepts of eternal recurrence.

The Nietzschean concepts were interesting (if not persuasive), but my favorite theme was Kundera’s treatment of the idea of compassion, which Kundera believed was “preeminent” of all human sentiments.

In languages derived from Latin, the word “compassion” is formed by combining the prefix “com” (with) and the noun “passio” (suffering). Other languages use words with a slightly different meaning—“feeling” instead of suffering. This, Kundera argued, gave the word even greater potency. Here is what he wrote:

To have compassion (co-feeling) means not only to be able to live with the other’s misfortune but also to feel with him any emotion- joy, anxiety, happiness, pain. This kind of compassion…therefore signifies the maximal capacity of affective imagination, the art of emotional telepathy. In the hierarchy of sentiments, then, it is supreme.

I thought of this passage after a conversation I had with my wife. I mentioned in passing that above anything else they do or become, I want our children to be compassionate–more than intelligence, athleticism, education, or riches.

It made me wonder: How does one acquire compassion? From where does it flow? Is it more through our nature or nurture? Do we learn it from example? From books? From religion?

Psychologists say mammals are born with compassion. That it’s an instinctive impulse that has helped humans evolve as a species. But if humans are born with compassion, how is it that history and psychology have observed so many humans without compassion? (Psychopaths, for example, often seem incapable of it.)

There are two possibilities: 1) some humans are not born with compassion; 2) humans are born with compassion but they are capable of losing or burying it.

Psychologists are likely right that mammals are born with traces of compassion. But rats paying attention to their dead or the eyes of human babies dilating while observing people helping one another is quite different from the “emotional telepathy” described by Kundera.

Compassion seems to be like a seed; it flowers in some people and dies in others. This would explain why Joseph Stalin could kill millions and erase his allies without compunction, while Nietzsche was driven mad by the sight of a horse being whipped.

Nietzsche’s fate helps explain the paradoxical nature of compassion.

Sharing the suffering of other creatures is a beautiful and noble thing. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer called it “the basis of all morality.”

But sharing the suffering of others in a world full of pain and misery is also a heavy burden. Perhaps this is why Kundera, who praised compassion as supreme in the hierarchy of sentiments, also called it a curse.

If humans allowed ourselves to feel the full spectrum of creature suffering in this fallen world, we probably would end up much like Nietzsche.

That said, I can think of few things this world needs more. Perhaps this is why I so desire my children to have compassion, even if it is a curse.

Indeed, as a Christian, I think it’s a burden we’re called to carry. This is why I’ve never been able to sneer at the works of people like Mother Teresa. We need compassion—real compassion, not faux compassion—in this world every bit as much as we need the earthly things that sustain us. Perhaps more.

Kundera understood compassion—its virtue and its curse—better than almost anyone, and he articulated in a way that didn’t just move me, but helped me understand it more deeply.

For that and much more, I’ll miss him and his writing.