I’m not a regular reader of Noah Smith, the “Noahpinion” blogger and journalist who writes on economics. Nor do I know him personally.

From what I know about him, I’d say he’s smart and a very effective writer. He’s relatively famous in writing circles (far more so than yours truly) and knows his stuff. Think of him as a slightly less influential version of Nate Silver—wonky, data-driven, and not shy about sharing his opinions.

One of the things that always bothered me about Smith was his disdain for libertarians (which I consider myself, small “l”). Like many progressives, he seemed infected with a (metaphorical) brain worm that prevented him from seeing common sense—things I’d take for granted.

I'm not even going to argue that I'm right about all of these things and that Smith is wrong. I've lived long enough to know that people are different—we perceive reality in different ways, carry distinct moral frameworks, and weigh truth and consequence through lenses shaped by experience, culture, and belief.

At some point—I don’t know exactly when—I became less concerned about winning arguments and more interested in trying to understand what others think, and why.

That doesn’t mean I don’t want to shape the world for the better (I do). Nor does it mean I don’t relish “winning” an argument. I’m not above, shall we say, spiking the football when appropriate.

Which brings me back to Noah Smith, who recently issued a public apology to libertarians.

You can read the previous criticisms and current caveats for yourself, but here’s the nut graph:

“…I feel like I owe libertarians an apology, for severely underrating their ideology. I was so focused on its theoretical flaws that I ignored its political importance. I concentrated only on the marginal benefits that might be achieved by building on our economic system’s libertarian foundation, ignoring the inframarginal losses that would happen were that foundation to crumble. I had only a hazy, poor understanding of the historical context in which libertarianism emerged, and of the limitations of libertarianism’s most prominent critics.”

I’d encourage readers to read the first sentence again, because it’s the most important part.

The biggest criticism I get—especially when talking to my progressive friends—is that libertarianism isn’t practical. Government already does all these things, and the idea that it’s going to stop doing them is, to them, unrealistic.

The second biggest objection I get is that it’s a flawed theory. Sophists can always find ways to poke holes in it, just as clever minds can undermine Scripture or any complex system of thought. But pointing out imperfections or morally complicated tradeoffs in an ideological framework isn’t the same as disproving it.

You can find theoretical flaws in any value system. And I’d argue that to the extent the left has succeeded, it has done so in the absence of a coherent value system (unless you count Utopianism as a value system).

What Smith learned was the political importance of libertarianism. The catalyst for his education was, of course, President Trump’s Liberation Day tariffs.

The size and breadth of Trump’s tariffs came as a shock to me. I never imagined that a U.S. leader would have such a deeply broken view of how trade works, or would willfully inflict such harm on the American people. But I should have known it was possible. I should have studied the historical example of Juan Peron, whose Trump-style policies of protectionism and fiscal profligacy combined to knock Argentina out of the ranks of the rich nations. I should have studied the failure of “import substitution” policies in the 1950s and 1960s. I should have known more about the political context that produced Smoot-Hawley in the U.S.

I should also have realized that as right-leaning ideologies go, American libertarianism was always highly unusual. I had lived in Japan, where the political right is protectionist, industrialist, and sometimes crony-capitalist. I should have realized that this was the norm for right-leaning parties around the world, and that the American right’s Reaganite embrace of free markets and free trade was the anomaly. That, in turn, should have given me a warning of what would happen if libertarianism fell in America.

I did not understand the relevant pieces of history, nor did I think carefully enough about what I had observed overseas.

I don’t have a PhD in economics, but I do have a couple degrees in history. And Smith is right: history doesn’t whisper about the consequences of protectionism—it shouts. Over and again, we’ve seen how trade barriers, however well-intentioned, lead to retaliation, inefficiency, and long-term economic harm.

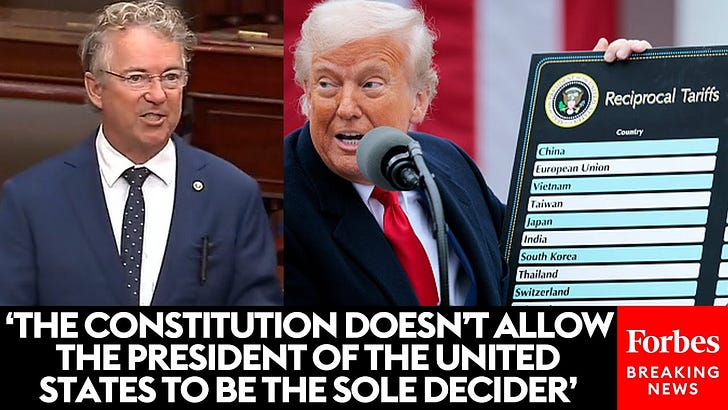

And who in the Republican Party is speaking out? Rand Paul. This was not lost on Smith.

“The spectacle of a libertarian Republican standing up to a President who holds near-absolute power within the GOP is inspiring,” he writes.

I agree. It is inspiring. But I also agree that Paul’s opposition (even with the help of Senate Democrats) may not be enough to stop the protectionist tide. To say that his worries me is an understatement.

It was Marx who told us (or was it Hegel?) that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce.

I worry we're entering the farce stage—but I'm encouraged to see Noah Smith giving serious reconsideration to old ideas. Ideas have consequences. And I fear we’re about to learn that.

P.S. Read what economist Nils Hesse has to say about the populist logic behind Trump’s tariffs.

P.P.S. Read what my friend and colleague Pete Earle does some back-of-the-envelope calculations on the proposal to use tariffs as tax reform. (The math is not good.)

Bravo Rand Paul.

Is he actually standing on a libertarian position here in any way?

I’m asking in interest of clarifying my concept of libertarianism.

It takes moral character to issue a mea culpa like that. Kudos to Noah!